Each bird has a metal ring on the left leg and a plastic colour ring on the right leg. The rings do not hurt the birds nor do they worry them in any way. Rings are only allowed to be put on birds by licensed ringers, which for our project are Michel Beaud, Adrian Aebischer and Roy Dennis. The metal ring on the left leg is provided by the Swiss Ornithological Station (SOS) at Sempach and has a unique number. If someone finds a ringed bird they can inform the SOS who will then tell us that someone has seen the bird.

Each bird has a metal ring on the left leg and a plastic colour ring on the right leg. The rings do not hurt the birds nor do they worry them in any way. Rings are only allowed to be put on birds by licensed ringers, which for our project are Michel Beaud, Adrian Aebischer and Roy Dennis. The metal ring on the left leg is provided by the Swiss Ornithological Station (SOS) at Sempach and has a unique number. If someone finds a ringed bird they can inform the SOS who will then tell us that someone has seen the bird.

To be able to read the metal ring you usually need to have captured the bird. However, on the right leg we put a larger plastic colour ring which can be read more easily when the bird if flying or perched, usually with a telescope or a telephoto camera lens. Each bird has a unique code and in 2015 we put blue rings with the white letters PP followed by a number (PP1, PP2, up to PP6) on the right leg. These rings were already placed on the birds in Scotland so that they were identifiable when they were brought into Switzerland, and the numbers were included on their CITES export and import permits.

Note that blue colour rings are also used for Ospreys in the UK, but these have different combinations of letters and numbers and are placed on the left leg. Therefore, if anyone sees an Osprey with a blue ring on its right leg, it is an Osprey that has been reintroduced to Switzerland. The birds are named after the letters and numbers on their blue plastic ring.

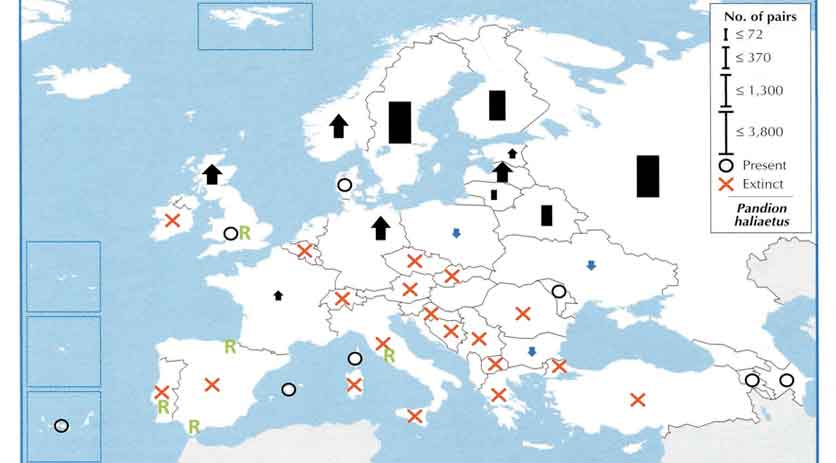

The reason that it is very unlikely (with nature you can never say impossible, but we can say very unlikely) that the Osprey will start breeding in western Switzerland again without help is due to “philopatry”. Philopatry is the tendency of an individual to stay or to return to the place where they were born in order to breed. Some species, like the Osprey, have a very strong philopatry, which results in a very limited ability to disperse to new areas. This means that when a population disappears, it is exceedingly unlikely that individuals who were not born in this area will recolonise it, even if suitable habitat exists.

The reason that it is very unlikely (with nature you can never say impossible, but we can say very unlikely) that the Osprey will start breeding in western Switzerland again without help is due to “philopatry”. Philopatry is the tendency of an individual to stay or to return to the place where they were born in order to breed. Some species, like the Osprey, have a very strong philopatry, which results in a very limited ability to disperse to new areas. This means that when a population disappears, it is exceedingly unlikely that individuals who were not born in this area will recolonise it, even if suitable habitat exists.